Week 4: April 11- April 16, 2016

After coming back from Italy, I took a day to decompress and think about my personal goals for the fellowship and begin to sketch out what I would like to learn during my time here and focus on. We also had our monthly check-in call with all the fellows to chat about our first few weeks! It was so great to see everyone.

This week, I spent a few days working on looking at data on nursing homes throughout Germany for our upcoming investigation which publishes in June. Since I don’t know much German, and I especially don’t understand German government words, it was really hard. At first, I tried to look at each spreadsheet (which were organized by state) and try to translate each and every word. That proved to be a lot of work and probably not a good use of my time.

Then, I asked my colleague, Simon to help me get a basic grasp of the data. First, I went searching for a map of Germany and the 16 states so I could understand the data that I am looking at. Then I spent a fair bit of time reading on the German statistics website what the different data are.

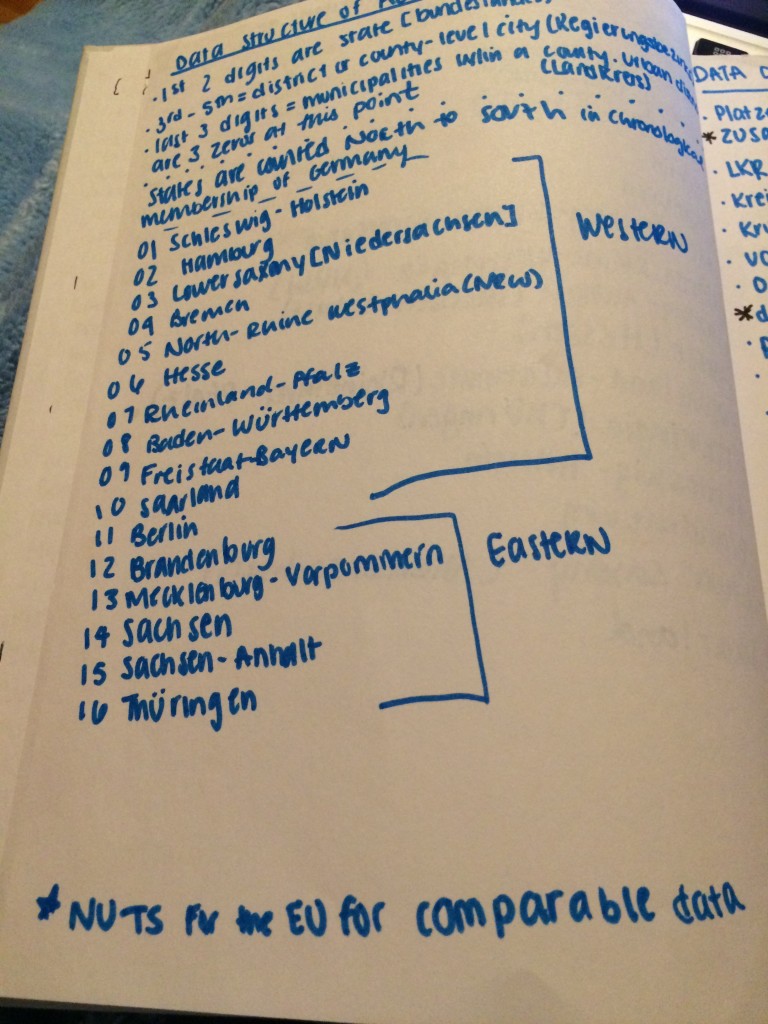

I created this guide (b/c I’m a visual person & writing things down really help me remember them).

What I learned:

- There are 16 states in Germany and some of them like Niedersachsen (Lower Saxony) and Sachsen (Saxony) have different names in English and German. The states in Germany are each given a number (as seen in my notes above) and they are counted in North to South in chronological membership in Germany.

- The main website for Census data (latest is 2011) is the Statistisches Bundesamt. Once you download the data, you’ll see that there is a column with the state number (column A), followed by the Bundesland (name of the federal state), and the Amtlicher Gemeinde-schlüssel (AGS). The AGS is the Official municipality key, which basically is a sequence of numbers that are used to identify areas in German government datasets.

- A quick overview of the AGS data: it consists of 8 digits, which are as follows:

- 1st two digits are the state or the Bundeslandes (in the notes above)

- 3rd to 5th digits are the district or the county-level city (Regierungsbezirke)

- 6th thru 8th digits are the municipalities within a county. Urban districts are three zeros at this point.

- In the European Union, there is the NUTS (Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics) which is used to uniquely identify units of official statistics in the member states of the EU.

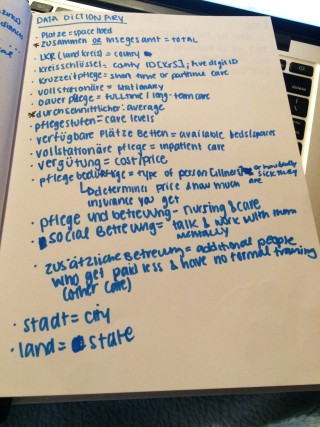

After looking through this, I created a data dictionary for the common words that I kept finding over and over again in the spreadsheets. One thing that threw me off was stadt and land because for some reason I assumed (never good to do that!) that stadt was state because of the similarity of the words. I’ve written this one a few times to remember it.

Some helpful words that I learned:

- durchschnittlicher: average

- zusammen or insegesamt: total

- stadt: city

- land: state

- dauerpflege: long-term care

The U.S. and Great Britain are among a few places to use a period to indicate decimals. Other countries, such as Germany use a comma instead. So when I pull the data into R or SQL, it was confusing to me because my preferences for thousand separators were set to the U.S. way.

So what does this mean exactly? Well, in the U.S. you would write 4,123,123,123.50 and in Germany you would write 4 123 123. 123,50.

That threw me for a loop for a day or so, but I think I’m beginning to get a grasp on that.

This week I also learned about something near and dear to my interests: the FOI (Freedom of Information laws) for Germany. I thought I’d share what I learned.

- Used for obtaining documents

- One law for federal agencies, not all state have laws

- Main exemptions: public interests, security, military security; trade secrets/internal information central to a business; or intellectual property

- They have to answer your request in a 1 month period; If not, write an appeal (send it by fax or mail it)

- There is a Commissioner for Data Protection – similar to an ombudsman in evey state; contact this person when you are appealing something.

- Maximum charge for one request would be 500 euros

- Can always go in person if you want the data and scanning laws are different

There is also something called the Press Law. It can be used for simple information over the phone that a reporter might be looking for. You’d have to contact the press authority. It’s a good starting point, as you can ask about some data and where it might be. You should always keep notes on what you’re working on and when you called them (as with any other FOI you’d file in any country).

There is also something called an “aktenplan” or a filing plan that every governmental branch and organization has to keep. They essentially describe the all of the files that they keep, including the order of the files. In most municipalities, they use the breakdown of 0-9 to file their materials. So if you were requesting data, you could look in the aktenplan for the given organization and then look through it to find the section you think the data might be stored in that you are looking for. You would then submit a FOI with the number of the section and subsection.

Comments are closed.